I’m writing this review at my work-at-home desk during the 2020 COVID lockdown, and ironically the first translation Google gives me for “scoppio” is “outbreak.” The second translation (from Italian) is explosion, which is more likely what WE Scoppio designer Toni N. Tietzel had in mind. The German designer’s logo is his initials on a little stick of dynamite. The star of this show is the blade’s unique (explosive?) compound grind. I’ve never seen anything quite like it, and as soon as I saw it, I knew I was going to buy this knife.

Buy the Scoppio at BladeHQ or GP Knives

Back in the olden times when I actually physically worked in a building that wasn’t my house, I showed the Scoppio to my two knife-lovin’ co-workers, and I noticed something interesting: several non-knife people wanted to touch it. It’s generally been my experience that most… how do I say this nicely? Most… indoor-oriented people act like if they pick up a folding knife it’s going to bite them like a rattlesnake.

But the Scoppio, which is not small or meek looking, elicited an unprecedented amount of interest. They were drawn to its unusual-looking handle design, its unexpectedly heavy weight in the hand, and definitely by its rich, sparkly blue stonewashed color. My appreciation of this knife goes significantly deeper than that, and it starts with the basic specs:

General Dimensions and Blade Details

The Scoppio has a 3.6” (92 mm) long drop point blade that’s .16” (4 mm) thick, and has a deep stonewash finish. Mine has blue titanium handle scales and a gray blade, but there are black, bronze, and gray handled versions available, some with black stonewashed blades. The open length is 8.18” (208 mm) and my medium-large hands can get a comfortable four-finger grip on the Scoppio when open. All versions run around $259.00 online.

The blade is CPM-20CV stainless steel, which is the sort of premium knife steel that’s expected in this price range. According to smart people who understand steel, CPM-20CV is virtually identical to the more well-known Bohler M390 steel. The main difference is M390 is made in Austria, and CPM-20CV is made in America.

So the Scoppio was designed by a German, the name is Italian, the blade steel is American, and the whole thing is assembled in Yangjiang, China. If I may digress for a moment, the city of Yangjiang is home to a remarkable number of knife companies. Higher-end makers include Reate, Kizer, Bestech, Rike, and Artisan Cutlery, in addition to WE and it’s less fancy sister company, Civivi. It’s like a Chinese version of European knife-producing cities like Solingen, Germany or Maniago, Italy, but undoubtedly a thousand times larger. End of digression.

CPM-20CV has a Rockwell Hardness (HRC) rating between 59 and 61, which is excellent in terms of edge retention, AKA hardness. The tradeoff of a high hardness rating is usually a lower “toughness” rating, meaning that if you whack the cutting edge of the blade with a hammer, the blade is more likely to chip than dent. That’s a tradeoff I’m happy to live with, since I would rather take the risk of a chipped blade over having to sharpen it more often, like I would have to with a less hard steel with a higher toughness rating. CPM-20CV’s 59-61 HRC is nothing compared to Sandrin Knives tungsten carbide blades which reach 71 HRC, but again, the tradeoff of that much hardness means a brittle blade.

The Scoppio’s blade has a lot going on design-wise, starting with it’s overall shape.

It’s a drop point with an unusually big belly that dips a little lower in the middle than at its base. The Scoppio’s belly is one of the many small, unconventional touches that make this knife so fascinating to me. The spine of the blade, for example, is neither a straight line nor a gentle, unbroken curve like on most knives. From tail to tip, it constantly changes angles and thicknesses. And the grind on the flat of the blade is bonkers. The multi-angled grind reminds me of the work of knife design genius Geoff Blauvelt of TuffKnives. He often does interesting 3-D grinds, and Strider Knives has what they call the “Nightmare Grind”, but both strike me as kind of aggressive-looking and seem designed to draw my eye towards the blade tip. The Scoppio’s grind just looks weird. Good weird for sure, but weird.

The unique grind doesn’t seem to impede cutting, but it is a thick blade. Slicing through a crisp apple, the thick top of the blade stock eventually ends up splitting the apple open like a wedge. The Scoppio was my only food prep tool at the 2020 SHOT Show, and I used it daily as a bread slicer, vegetable chopper, and Vegan-aise spreader. By the way, I can tell you from personal experience that it’s virtually impossible to find vegan food at the Shooting Hunting Outdoors Trade show. The Scoppio performed hotel room kitchen duties a little better than a typical flipper-opening knife due to the blade’s belly, but the flipper tab extends well below the blade, so dicing and chopping required a rocking motion, which is less than ideal. Next year I’m bringing a real kitchen knife and a cutting board.

Handle, Ergonomics, and Pocket Clip

The show side of the handle, like the blade, has a standout feature: no visible screws. The “WE” logo hides the knife’s pivot, and it’s flush with the handle scales so the knife has zero wobble when laid flat- a nice touch.

At first glance, it looks rather plain, but upon closer inspection it’s full of subtle curves and unexpected angles. My favorite example of this on the Scoppio are the side-by-side vertices (basically the corners) at the butt end of the handle.

The rearmost vertex (1) follows a logical, normal path by having its corner centered at the apex of the curve. It’s symmetrical and looks “correct” to the eye. The vertex right next to it, however, (2) goes off at a weird angle.

The eye expects vertex 2 to go in the direction the orange arrow is pointing, but instead of being normal looking, its corner angle veers off to the right. I think the design principle this violates is called isometric angle symmetry, but I don’t know anyone who can answer obscure geometry questions. The robust, milled pocket clip’s shape is a (hopefully) easier to grasp example of the strangeness of the Scoppio’s design.

The clip, starting near the tip, is a uniform width. It goes along a predictable curve, as illustrated by the orange lines. Then it gets to the screws, where it looks like it got bent and sliced off with a razor blade. The eye expected it to finish its nice curve, but designer Toni M. Tietzel said no! to that expectation. The entire knife has interesting curvy lines and strange angles, and I absolutely love how unique it is.

I mentioned at the top of the review that non-knife people showed a lot of interest in this knife, and I think one of the factors was that it feels much heavier than you’d expect for something this size. Everyone immediately tossed it up and down in their hand and remarked on the weight. The Scoppio’s bladestock and titanium handle scales are each 4 mm thick on the sides, and where the two pieces meet on the top to form a closed-back design, it’s a total of 13 mm across. The heft of this knife made me aware that titanium isn’t nearly as light as I thought it was. I have other knives that weigh more than the Scoppio’s 4.6 oz (131 gm) but this knife just feels heavier than it looks.

I think the Scoppio’s ergonomics are good- the clip is comfortable against my hand in any grip, the edges of its smooth handle scales are all nicely chamfered so there are no noticeable hot spots, and it’s long and wide enough for me be able to wrap my fingers around it, resulting in a solid grip. It gets slippery when my hands are wet, but I find most folding knives to be hard to hang onto with wet hands.

I’ve noticed that, when dry, smooth titanium feels grippier than smooth aluminum, and that textured G10 and micarta are grippy by nature. I assumed good wet knife retention to be a function of the handle material or how much traction is milled into the handles. I take the thoroughness of my reviews somewhat seriously, so I brought 10 of my folding knives over to the kitchen sink and opened, closed, and manipulated them all with wet hands. I had handles made of machined carbon fiber, machined G10, textured G10, aluminum, copper, smooth titanium, and heavily machined titanium. Surprisingly, the slippery-hands knife retention winner was my GiantMouse Knives GM1.

The GM1 (center of picture) is the smoothest, flattest titanium knife I own, but it also has the most pronounced index finger groove. It turns out that finger grooves work really well with wet hands. The finger groove kept my hand from sliding back and forth, and slipperiness barely affected my grip. The Scoppio’s flipper tab kept my index finger from sliding forward onto the blade, but there’s not much in the handle shape to keep the knife from slipping out of my hand in the other direction should I ever have to hack open an old-fashioned gallon can of olive oil.

Deployment and Lockup

The Scoppio didn’t win the wet knife handle contest, but it definitely wins the best lock engagement sound award. It’s a superbly satisfying steel-on-steel clack, and I’ve never heard its equal in the flipper knife world. I don’t know if it was by accident or design, but WE Knife Co. got the harmonics just right with the Scoppio. It may be connected to the fact that the designer ignored the modern trend of milling weight-reducing pockets into the inside of the thick titanium handles. But whatever the cause, the overall result is a meaty snap when the Scoppio is flipped open on its ceramic bearings.

I have a huge, stainless steel 44 Magnum revolver that weighs 3-1/2 pounds, and the sound of quickly thumb-cocking it is the closest parallel I can think of to snapping open the Scoppio.

The flipping action is smooth and very well-balanced, and the small flipper tab has a little jimping on the front to give my index finger some traction. Lockup on mine is at 30%, which I would usually think of as inadequate, but there’s no arguing with the clack- it’s locked open tight. One contributing factor to the tight lockup may be the blade-mounted stop pin pictured below.

A stop pin (as I understand it) is a typically cylindrical piece of steel inside a folding knife’s handle that the butt end of the blade rests on when it’s open. Its function is basically to keep the blade from opening too far, and to keep the blade in the exact right place when it’s open. On most of my knives, the stop pin is mounted inside the knife between the handles. On the Scoppio, the stop pin is attached to the blade, and it rides in little grooves machined into the handles. I read online that blade-mounted stop pins like this can help reduce side-to-side blade wiggle. I don’t know if that’s true, or if one kind of stop pin system is superior, but frankly it’s too boring for me to investigate further.

WE Knife Co. Scoppio Review – Final Thoughts

This has been a thoroughly positive review up to this point, but according to the sacred code of the reviewer, I have to find something negative to say…OK, I wish the pocket clip screwed into the handle from the inside so the screws wouldn’t be visible, giving the Scoppio an even cleaner look.

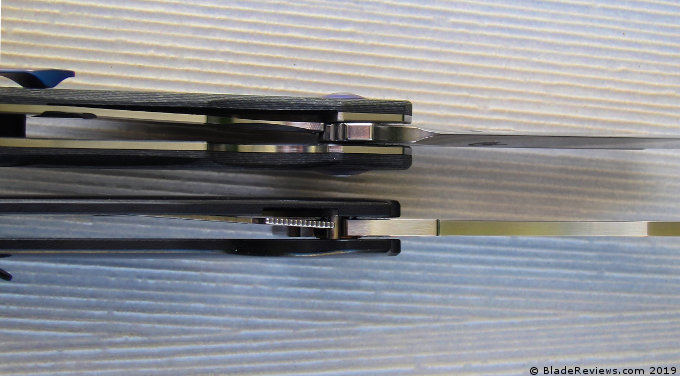

And speaking of clean looks, the Scoppio has quite a noticeable seam where the two sides meet. I’m not saying that the Scoppio isn’t well made, but look at where the two halves of the handle meet on the Reate Knives Starboy pictured above- now that’s a seamless seam.

That’s all the negativity I can muster. I love this knife. Its lines and angles are strange and unpredictable, yet it’s not some unusable art piece. The three knives pictured below are by three different designers, but what they all have in common is weird contours and shapes that I find fascinating.

The bottom knife is the Microtech Cypher, designed by Deryk “D.C.” Munroe. It’s like a piece of petrified wood with a huge knife blade that shoots out the front. Everything about it is a little wrong, and I find it endlessly fascinating. On top is the Bestech Marukka, designed by Grzegorz “Kombou” Grabarski. There are so many neat bio-mechanical twists and turns on this brand-new knife that I had to bump it to the top of my BladeReviews review queue. The WE Scoppio, along with the other knives in the picture, are functional art. At the risk of sounding sappy, these three have inspired me to take a stab at designing knives. It’s finally time to turn the sketches and notes I’ve been collecting for years into something in SolidWorks. The Scoppio is both inspired and inspiring, and I highly recommend it.

We Knives Scoppio – $259.25

From: BladeHQ

I recommend purchasing the We Knives 605J at BladeHQ and GP Knives. Purchasing anything through any of the links on this site helps support BladeReviews, and keep this review train running. As always, any and all support is greatly appreciated.